PORTO BELLO AND PANAMA

On 4th January 1664, the king

wrote to Sir Thomas Modyford in

Barbadoes that he had chosen him

governor of Jamaica.206

Modyford, who had lived as a planter

in Barbadoes since 1650, had taken a

prominent share in the struggles

between Parliamentarians and

Royalists in the little island. He

was a member of the Council, and had

been governor for a short time in

1660. His commission and

instructions for Jamaica207

were carried to the West Indies by

Colonel Edward Morgan, who went as

Modyford's deputy-governor and

landed in Barbadoes on 21st April.208

Modyford was instructed, among other

things, to prohibit the granting of

letters of marque, and particularly

to encourage trade and maintain

friendly relations with the Spanish

dominions. Sir Richard Fanshaw had

just been appointed to go to Spain

and negotiate a treaty for wider

commercial privileges in the Indies,

and Charles saw that the daily

complaints of violence and

depredation done by Jamaican ships

on the King of Spain's subjects were

scarcely calculated to increase the

good-will and compliance of the

Spanish Court. Nor had the attempt

in the Indies to force a trade upon

the Spaniards been brilliantly

successful. It was soon evident that

another course of action was

demanded. Sir Thomas Modyford seems

at first to have been sincerely anxious to suppress

privateering and conciliate his

Spanish neighbours. On receiving his

commission and instructions he

immediately prepared letters to the

President of San Domingo, expressing

his fair intentions and requesting

the co-operation of the Spaniards.209

Modyford himself arrived in Jamaica

on 1st June,210

proclaimed an entire cessation of

hostilities,211

and on the 16th sent the "Swallow"

ketch to Cartagena to acquaint the

governor with what he had done. On

almost the same day letters were

forwarded from England and from

Ambassador Fanshaw in Madrid,

strictly forbidding all violences in

the future against the Spanish

nation, and ordering Modyford to

inflict condign punishment on every

offender, and make entire

restitution and satisfaction to the

sufferers.212

The letters for San Domingo,

which had been forwarded to Jamaica

with Colonel Morgan and thence

dispatched to Hispaniola before

Modyford's arrival, received a

favourable answer, but that was

about as far as the matter ever got.

The buccaneers, moreover, the

principal grievance of the

Spaniards, still remained at large.

As Thomas Lynch wrote on 25th May,

"It is not in the power of the

governor to have or suffer a

commerce, nor will any necessity or

advantage bring private Spaniards to

Jamaica, for we and they have used

too many mutual barbarisms to have a

sudden correspondence. When the king

was restored, the Spaniards thought

the manners of the English nation

changed too, and adventured twenty

or thirty vessels to Jamaica for

blacks, but the surprises and

irruptions by C. Myngs, for whom the

governor of San Domingo has

upbraided the commissioners, made

the Spaniards redouble their malice,

and nothing but an order from Spain

can give us admittance or

trade."213

For a short time, however, a serious

effort was made to recall the

privateers. Several prizes which

were brought into Port Royal were

seized and returned to their owners,

while the captors had their

commissions taken from them. Such

was the experience of one Captain

Searles, who in August brought in

two Spanish vessels, both of which

were restored to the Spaniards, and

Searles deprived of his rudder and

sails as security against his making

further depredations upon the Dons.214

In November Captain Morris Williams

sent a note to Governor Modyford,

offering to come in with a rich

prize of logwood, indigo and silver,

if security were given that it

should be condemned to him for the

payment of his debts in Jamaica; and

although the governor refused to

give any promises the prize was

brought in eight days later. The

goods were seized and sold in the

interest of the Spanish owner.215

Nevertheless, the effects of the

proclamation were not at all

encouraging. In the first month only

three privateers came in with their

commissions, and Modyford wrote to

Secretary Bennet on 30th June that

he feared the only effect of the

proclamation would be to drive them

to the French in Tortuga. He

therefore thought it prudent, he

continued, to dispense somewhat with

the strictness of his instructions,

"doing by degrees and moderation

what he had at first resolved to

execute suddenly and severely."216

Tortuga was really the crux of

the whole difficulty. Back in 1662

Colonel Doyley, in his report to the

Lord Chancellor after his return to

England, had suggested the reduction of Tortuga to

English obedience as the only

effective way of dealing with the

buccaneers;217

and Modyford in 1664 also realized

the necessity of this preliminary

step.218

The conquest of Tortuga, however,

was no longer the simple task it

might have been four or five years

earlier. The inhabitants of the

island were now almost entirely

French, and with their companions on

the coast of Hispaniola had no

intention of submitting to English

dictation. The buccaneers, who had

become numerous and independent and

made Tortuga one of their principal

retreats, would throw all their

strength in the balance against an

expedition the avowed object of

whose coming was to make their

profession impossible. The colony,

moreover, received an incalculable

accession of strength in the arrival

of Bertrand d'Ogeron, the governor

sent out in 1665 by the new French

West India Company. D'Ogeron was one

of the most remarkable figures in

the West Indies in the second half

of the seventeenth century. Of broad

imagination and singular kindness of

heart, with an indomitable will and

a mind full of resource, he seems to

have been an ideal man for the task,

not only of reducing to some

semblance of law and order a people

who had never given obedience to any

authority, but also of making

palatable the régime and

exclusive privileges of a private

trading company. D'Ogeron first

established himself at Port Margot

on the coast of Hispaniola opposite

Tortuga in the early part of 1665;

and here the adventurers at once

gave him to understand that they

would never submit to any mere

company, much less suffer an

interruption of their trade with the

Dutch, who had supplied them with

necessities at a time when it was

not even known in France that there

were Frenchmen in that region. D'Ogeron pretended to

subscribe to these conditions,

passed over to Tortuga where he

received the submission of la Place,

and then to Petit-Goave and Leogane,

in the cul-de-sac of

Hispaniola. There he made his

headquarters, adopted every means to

attract planters and engagés,

and firmly established his

authority. He made advances from his

own purse without interest to

adventurers who wished to settle

down to planting, bought two ships

to facilitate trade between the

colony and France, and even

contrived to have several lots of

fifty women each brought over from

France to be sold and distributed as

wives amongst the colonists. The

settlements soon put on a new air of

prosperity, and really owed their

existence as a permanent French

colony to the efforts of this new

governor.219

It was under the administration of

d'Ogeron that l'Olonnais,220

Michel le Basque, and most of the

French buccaneers flourished, whose

exploits are celebrated in

Exquemelin's history.

The conquest of Tortuga was not

the only measure necessary for the

effectual suppression of the

buccaneers. Five or six swift

cruisers were also required to

pursue and bring to bay those

corsairs who refused to come in with

their commissions.221

Since the Restoration the West

Indies had been entirely denuded of

English men-of-war; while the

buccaneers, with the tacit consent

or encouragement of Doyley, had at

the same time increased both in

numbers and boldness. Letters

written from Jamaica in 1664 placed

the number scattered abroad in

privateering at from 1500 to 2000,

sailing in fourteen or fifteen

ships.222

They were desperate men, accustomed

to living at sea, with no trade but

burning and plundering, and unlikely to take orders from any

but stronger and faster frigates.

Nor was this condition of affairs

surprising when we consider that, in

the seventeenth century, there

flowed from Europe to the West

Indies adventurers from every class

of society; men doubtless often

endowed with strong personalities,

enterprising and intrepid; but

often, too, of mediocre intelligence

or little education, and usually

without either money or scruples.

They included many who had revolted

from the narrow social laws of

European countries, and were

disinclined to live peaceably within

the bounds of any organized society.

Many, too, had belonged to

rebellious political factions at

home, men of the better classes who

were banished or who emigrated in

order to keep their heads upon their

shoulders. In France the total

exhaustion of public and private

fortune at the end of the religious

wars disposed many to seek to recoup

themselves out of the immense

colonial riches of the Spaniards;

while the disorders of the Rebellion

and the Commonwealth in England

caused successive emigrations of

Puritans and Loyalists to the newer

England beyond the seas. At the

close of the Thirty Years' War, too,

a host of French and English

adventurers, who had fattened upon

Germany and her misfortunes, were

left without a livelihood, and

doubtless many resorted to

emigration as the sole means of

continuing their life of freedom and

even of licence. Coming to the West

Indies these men, so various in

origin and character, hoped soon to

acquire there the riches which they

lost or coveted at home; and their

expectations deceived, they often

broke in a formal and absolute

manner the bonds which attached them

to their fellow humanity. Jamaica

especially suffered in this respect,

for it had been colonized in the

first instance by a discontented,

refractory soldiery, and it was

being recruited largely by

transported criminals and vagabonds.

In contrast with the policy of

Spain, who placed the most careful

restrictions upon the class of

emigrants sent to her American

possessions, England from the very

beginning used her colonies, and

especially the West Indian islands,

as a dumping-ground for her refuse

population. Within a short time a

regular trade sprang up for

furnishing the colonies with servile

labour from the prisons of the

mother country. Scots captured at

the battles of Dunbar and Worcester,223

English, French, Irish and Dutch

pirates lying in the gaols of

Dorchester and Plymouth,224

if "not thought fit to be tried for

their lives," were shipped to

Barbadoes, Jamaica, and the other

Antilles. In August 1656 the Council

of State issued an order for the

apprehension of all lewd and

dangerous persons, rogues, vagrants

and other idlers who had no way of

livelihood and refused to work, to

be transported by contractors to the

English plantations in America;225

and in June 1661 the Council for

Foreign Plantations appointed a

committee to consider the same

matter.226

Complaints were often made that

children and apprentices were

"seduced or spirited away" from

their parents and masters and

concealed upon ships sailing for the

colonies; and an office of registry was

established to prevent this abuse.227

In 1664 Charles granted a licence

for five years to Sir James

Modyford, brother of Sir Thomas, to

take all felons convicted in the

circuits and at the Old Bailey who

were afterwards reprieved for

transportation to foreign

plantations, and to transmit them to

the governor of Jamaica;228

and this practice was continued

throughout the whole of the

buccaneering period.

Privateering opened a channel by

which these disorderly spirits,

impatient of the sober and laborious

life of the planter, found an

employment agreeable to their

tastes. An example had been set by

the plundering expeditions sent out

by Fortescue, Brayne and Doyley, and

when these naval excursions ceased,

the sailors and others who had taken

part in them fell to robbing on

their private account. Sir Charles

Lyttleton, we have seen, zealously

defended and encouraged the

freebooters; and Long, the historian

of Jamaica, justified their

existence on the ground that many

traders were attracted to the island

by the plunder with which Port Royal

was so abundantly stocked, and that

the prosperity of the colony was

founded upon the great demand for

provisions for the outfit of the

privateers. These effects, however,

were but temporary and superficial,

and did not counterbalance the

manifest evils of the practice,

especially the discouragement to

planting, and the element of

turbulence and unrest ever present

in the island. Under such conditions

Governor Modyford found it necessary

to temporise with the marauders, and

perhaps he did so the more readily

because he felt that they were still

needed for the security of the

colony. A war between England and

the States-General then seemed

imminent, and the governor

considered that unless he allowed

the buccaneers to dispose of their

booty when they came in to

Port Royal, they might, in event of

hostilities breaking out, go to the

Dutch at Curaçao and other islands,

and prey upon Jamaican commerce. On

the other hand, if, by adopting a

conciliatory attitude, he retained

their allegiance, they would offer

the handiest and most effective

instrument for driving the Dutch

themselves out of the Indies.229

He privately told one captain, who

brought in a Spanish prize, that he

only stopped the Admiralty

proceedings to "give a good relish

to the Spaniard"; and that although

the captor should have satisfaction,

the governor could not guarantee him

his ship. So Sir Thomas persuaded

some merchants to buy the

prize-goods and contributed one

quarter of the money himself, with

the understanding that he should

receive nothing if the Spaniards

came to claim their property.230

A letter from Secretary Bennet, on

12th November 1664, confirmed the

governor in this course;231

and on 2nd February 1665, three

weeks before the declaration of war

against Holland, a warrant was

issued to the Duke of York, High

Admiral of England, to grant,

through the colonial governors and

vice-admirals, commissions of

reprisal upon the ships and goods of

the Dutch.232

Modyford at once took advantage of

this liberty. Some fourteen pirates,

who in the beginning of February had

been tried and condemned to death,

were pardoned; and public

declaration was made that

commissions would be granted against

the Hollanders. Before nightfall two

commissions had been taken out, and

all the rovers were making

applications and planning how to

seize Curaçao.233

Modyford drew up an elaborate design234

for rooting out at one and the same

time the Dutch settlements and the

French buccaneers, and on 20th April

he wrote that

Lieutenant-Colonel Morgan had sailed

with ten ships and some 500 men,

chiefly "reformed prisoners,"

resolute fellows, and well armed

with fusees and pistols.235

Their plan was to fall upon the

Dutch fleet trading at St. Kitts,

capture St. Eustatius, Saba, and

perhaps Curaçao, and on the homeward

voyage visit the French settlements

on Hispaniola and Tortuga. "All this

is prepared," he wrote, "by the

honest privateer, at the old rate of

no purchase no pay, and it will cost

the king nothing considerable, some

powder and mortar-pieces." On the

same day, 20th April, Admiral de

Ruyter, who had arrived in the

Indies with a fleet of fourteen

sail, attacked the forts and

shipping at Barbadoes, but suffered

considerable damage and retired

after a few hours. At Montserrat and

Nevis, however, he was more

successful and captured sixteen

merchant ships, after which he

sailed for Virginia and New York.236

The buccaneers enrolled in

Colonel Morgan's expedition proved

to be troublesome allies. Before

their departure from Jamaica most of

them mutinied, and refused to sail

until promised by Morgan that the

plunder should be equally divided.237

On 17th July, however, the

expedition made its rendezvous at

Montserrat, and on the 23rd arrived

before St. Eustatius. Two vessels

had been lost sight of, a third,

with the ironical name of the "Olive

Branch," had sailed for Virginia,

and many stragglers had been left

behind at Montserrat, so that Morgan

could muster only 326 men for the

assault. There was only one

landing-place on the island, with a

narrow path accommodating but two

men at a time leading to an eminence

which was crowned with a fort and

450 Dutchmen. Morgan landed his

division first, and Colonel Carey

followed. The enemy, it seems, gave

them but one small volley and then

retreated to the fort. The governor

sent forward three men to parley,

and on receiving a summons to

surrender, delivered up the fort

with eleven large guns and

considerable ammunition. "It is

supposed they were drunk or mad,"

was the comment made upon the rather

disgraceful defence.238

During the action Colonel Morgan,

who was an old man and very

corpulent, was overcome by the hard

marching and extraordinary heat, and

died. Colonel Carey, who succeeded

him in command, was anxious to

proceed at once to the capture of

the Dutch forts on Saba, St. Martins

and Tortola; but the buccaneers

refused to stir until the booty got

at St. Eustatius was divided—nor

were the officers and men able to

agree on the manner of sharing. The

plunder, besides guns and

ammunition, included about 900

slaves, negro and Indian, with a

large quantity of live stock and

cotton. Meanwhile a party of seventy

had crossed over to the island of

Saba, only four leagues distant, and

secured its surrender on the same

terms as St. Eustatius. As the men

had now become very mutinous, and on

a muster numbered scarcely 250, the

officers decided that they could not

reasonably proceed any further and

sailed for Jamaica, leaving a small

garrison on each of the islands.

Most of the Dutch, about 250 in

number, were sent to St. Martins,

but a few others, with some

threescore English, Irish and

Scotch, took the oath of allegiance

and remained.239

Encouraged by a letter from the

king,240

Governor Modyford continued his

exertions against the Dutch. In

January (?) 1666 two buccaneer

captains, Searles and Stedman, with

two small ships and only eighty men

took the island of Tobago, near

Trinidad, and destroyed everything

they could not carry away. Lord

Willoughby, governor of Barbadoes,

had also fitted out an expedition to

take the island, but the Jamaicans

were three or four days before him.

The latter were busy with their work

of pillage, when Willoughby arrived

and demanded the island in the name

of the king; and the buccaneers

condescended to leave the fort and

the governor's house standing only

on condition that Willoughby gave

them liberty to sell their plunder

in Barbadoes.241

Modyford, meanwhile, greatly

disappointed by the miscarriage of

the design against Curaçao, called

in the aid of the "old privateer,"

Captain Edward Mansfield, and in the

autumn of 1665, with the hope of

sending another armament against the

island, appointed a rendezvous for

the buccaneers in Bluefields Bay.242

In January 1666 war against

England was openly declared by

France in support of her Dutch

allies, and in the following month

Charles II. sent letters to his

governors in the West Indies and the

North American colonies, apprising

them of the war and urging them to

attack their French neighbours.243

The news of the outbreak of

hostilities did not reach Jamaica

until 2nd July, but already in

December of the previous year

warning had been sent out to the

West Indies of the coming rupture.244

Governor Modyford, therefore, seeing

the French very much increased in

Hispaniola, concluded that it was

high time to entice the buccaneers

from French service and bind them to

himself by issuing commissions

against the Spaniards. The French

still permitted the freebooters to

dispose of Spanish prizes in their

ports, but the better market

afforded by Jamaica was always a

sufficient consideration to attract

not only the English buccaneers, but

the Dutch and French as well.

Moreover, the difficulties of the

situation, which Modyford had

repeatedly enlarged upon in his

letters, seem to have been

appreciated by the authorities in

England, for in the spring of 1665,

following upon Secretary Bennet's

letter of 12th November and shortly

after the outbreak of the Dutch war,

the Duke of Albemarle had written to

Modyford in the name of the king,

giving him permission to use his own

discretion in granting commissions

against the Dons.245

Modyford was convinced that all the

circumstances were favourable to

such a course of action, and on 22nd

February assembled the Council. A

resolution was passed that it was to

the interest of the island to grant

letters of marque against the

Spaniards,246

and a proclamation to this effect

was published by the governor at

Port Royal and Tortuga. In the

following August Modyford sent home

to Bennet, now become Lord

Arlington, an elaborate defence of

his actions. "Your Lordship very

well knows," wrote Modyford, "how

great an aversion I had for the

privateers while at Barbadoes, but

after I had put His Majesty's orders

for restitution in strict execution,

I found my error in the decay of the

forts and wealth of this place, and

also the affections of this people

to His Majesty's service; yet I continued

discountenancing and punishing those

kind of people till your Lordship's

of the 12th November 1664 arrived,

commanding a gentle usage of them;

still we went to decay, which I

represented to the Lord General

faithfully the 6th of March

following, who upon serious

consideration with His Majesty and

the Lord Chancellor, by letter of

1st June 1665, gave me latitude to

grant or not commissions against the

Spaniard, as I found it for the

advantage of His Majesty's service

and the good of this island. I was

glad of this power, yet resolved not

to use it unless necessity drove me

to it; and that too when I saw how

poor the fleets returning from

Statia were, so that vessels were

broken up and the men disposed of

for the coast of Cuba to get a

livelihood and so be wholly

alienated from us. Many stayed at

the Windward Isles, having not

enough to pay their engagements, and

at Tortuga and among the French

buccaneers; still I forebore to make

use of my power, hoping their

hardships and great hazards would in

time reclaim them from that course

of life. But about the beginning of

March last I found that the guards

of Port Royal, which under Colonel

Morgan were 600, had fallen to 138,

so I assembled the Council to advise

how to strengthen that most

important place with some of the

inland forces; but they all agreed

that the only way to fill Port Royal

with men was to grant commissions

against the Spaniards, which they

were very pressing in ... and

looking on our weak condition, the

chief merchants gone from Port

Royal, no credit given to privateers

for victualling, etc., and rumours

of war with the French often

repeated, I issued a declaration of

my intentions to grant commissions

against the Spaniards. Your Lordship

cannot imagine what an universal

change there was on the faces of men

and things, ships repairing, great

resort of workmen and labourers to

Port Royal, many returning, many

debtors released out of prison, and the ships

from the Curaçao voyage, not daring

to come in for fear of creditors,

brought in and fitted out again, so

that the regimental forces at Port

Royal are near 400. Had it not been

for that seasonable action, I could

not have kept my place against the

French buccaneers, who would have

ruined all the seaside plantations

at least, whereas I now draw from

them mainly, and lately David

Marteen, the best man of Tortuga,

that has two frigates at sea, has

promised to bring in both."247

In so far as the buccaneers

affected the mutual relations of

England and Spain, it after all

could make little difference whether

commissions were issued in Jamaica

or not, for the plundering and

burning continued, and the harassed

Spanish-Americans, only too prone to

call the rogues English of whatever

origin they might really be,

continued to curse and hate the

English nation and make cruel

reprisals whenever possible.

Moreover, every expedition into

Spanish territory, finding the

Spaniards very weak and very rich,

gave new incentive to such

endeavour. While Modyford had been

standing now on one foot, now on the

other, uncertain whether to repulse

the buccaneers or not, secretly

anxious to welcome them, but fearing

the authorities at home, the

corsairs themselves had entirely

ignored him. The privateers whom

Modyford had invited to rendezvous

in Bluefield's Bay in November 1665

had chosen Captain Mansfield as

their admiral, and in the middle of

January sailed from the south cays

of Cuba for Curaçao. In the

meantime, however, because they had

been refused provisions which,

according to Modyford's account,

they sought to buy from the

Spaniards in Cuba, they had marched

forty-two miles into the island, and

on the strength of Portuguese

commissions which they held against

the Spaniards, had plundered and

burnt the town of Sancti Spiritus,

routed a body of 200 horse, carried some prisoners to the

coast, and for their ransom extorted

300 head of cattle.248

The rich and easy profits to be got

by plundering the Spaniards were

almost too much for the loyalty of

the men, and Modyford, hearing of

many defections from their ranks,

had despatched Captain Beeston on

10th November to divert them, if

possible, from Sancti Spiritus, and

confirm them in their designs

against Curaçao.249

The officers of the expedition,

indeed, sent to the governor a

letter expressing their zeal for the

enterprise; but the men still held

off, and the fleet, in consequence,

eventually broke up. Two vessels

departed for Tortuga, and four

others, joined by two French rovers,

sailed under Mansfield to attempt

the recapture of Providence Island,

which, since 1641, had been

garrisoned by the Spaniards and used

as a penal settlement.250

Being resolved, as Mansfield

afterwards told the governor of

Jamaica, never to see Modyford's

face until he had done some service

to the king, he sailed for

Providence with about 200 men,251

and approaching the island in the

night by an unusual passage among

the reefs, landed early in the morning, and

surprised and captured the Spanish

commander. The garrison of about 200

yielded up the fort on the promise

that they would be carried to the

mainland. Twenty-seven pieces of

ordnance were taken, many of which,

it is said, bore the arms of Queen

Elizabeth engraved upon them.

Mansfield left thirty-five men under

command of a Captain Hattsell to

hold the island, and sailed with his

prisoners for Central America. After

cruising along the shores of the

mainland, he ascended the San Juan

River and entered and sacked

Granada, the capital of Nicaragua.

From Granada the buccaneers turned

south into Costa Rica, burning

plantations, breaking the images in

the churches, ham-stringing cows and

mules, cutting down the fruit trees,

and in general destroying everything

they found. The Spanish governor had

only thirty-six soldiers at his

disposal and scarcely any firearms;

but he gathered the inhabitants and

some Indians, blocked the roads,

laid ambuscades, and did all that

his pitiful means permitted to

hinder the progress of the invaders.

The freebooters had designed to

visit Cartago, the chief city of the

province, and plunder it as they had

plundered Granada. They penetrated

only as far as Turrialva, however,

whence weary and footsore from their

struggle through the Cordillera, and

harassed by the Spaniards, they

retired through the province of

Veragua in military order to their

ships.252

On 12th June the buccaneers, laden

with booty, sailed into Port Royal.

There was at that moment no declared

war between England and Spain. Yet the

governor, probably because he

believed Mansfield to be justified,

ex post facto, by the issue

of commissions against the Spaniards

in the previous February, did no

more than mildly reprove him for

acting without his orders; and

"considering its good situation for

favouring any design on the rich

main," he accepted the tender of the

island in behalf of the king. He

despatched Major Samuel Smith, who

had been one of Mansfield's party,

with a few soldiers to reinforce the

English garrison;253

and on 10th November the Council in

England set the stamp of their

approval upon his actions by issuing

a commission to his brother, Sir

James Modyford, to be

lieutenant-governor of the new

acquisition.254

In August 1665, only two months

before the departure of Mansfield

from Jamaica, there had returned to

Port Royal from a raid in the same

region three privateer captains

named Morris, Jackman and Morgan.255

These men, with their followers,

doubtless helped to swell the ranks

of Mansfield's buccaneers, and it

was probably their report of the

wealth of Central America which

induced Mansfield to emulate their

performance. In the previous January

these three captains, still

pretending to sail under commissions

from Lord Windsor, had ascended the

river Tabasco, in the

province of Campeache, with 107 men,

and guided by Indians made a detour

of 300 miles, according to their

account, to Villa de Mosa,256

which they took and plundered. When

they returned to the mouth of the

river, they found that their ships

had been seized by Spaniards, who,

on their approach, attacked them 300

strong. The Spaniards, softened by

the heat and indolent life of the

tropics, were no match for one-third

their number of desperadoes, and the

buccaneers beat them off without the

loss of a man. The freebooters then

fitted up two barques and four

canoes, sailed to Rio Garta and

stormed the place with only thirty

men; crossed the Gulf of Honduras to

the Island of Roatan to rest and

obtain fresh water, and then

captured and plundered the port of

Truxillo. Down the Mosquito Coast

they passed like a devouring flame,

consuming all in their path.

Anchoring in Monkey Bay, they

ascended the San Juan River in

canoes for a distance of 100 miles

to Lake Nicaragua. The basin into

which they entered they described as

a veritable paradise, the air cool

and wholesome, the shores of the

lake full of green pastures and

broad savannahs dotted with horses

and cattle, and round about all a

coronal of azure mountains. Hiding

by day among the numerous islands

and rowing all night, on the fifth

night they landed near the city of

Granada, just a year before

Mansfield's visit to the place. The

buccaneers marched unobserved to the

central square of the city,

overturned eighteen cannon mounted

there, seized the magazine, and took and imprisoned in

the cathedral 300 of the citizens.

They plundered for sixteen hours,

then released their prisoners, and

taking the precaution to scuttle all

the boats, made their way back to

the sea coast. The town was large

and pleasant, containing seven

churches besides several colleges

and monasteries, and most of the

buildings were constructed of stone.

About 1000 Indians, driven to

rebellion by the cruelty and

oppression of the Spaniards,

accompanied the marauders and would

have massacred the prisoners,

especially the religious, had they

not been told that the English had

no intentions of retaining their

conquest. The news of the exploit

produced a lively impression in

Jamaica, and the governor suggested

Central America as the "properest

place" for an attack from England on

the Spanish Indies.257

Providence Island was now in the

hands of an English garrison, and

the Spaniards were not slow to

realise that the possession of this

outpost by the buccaneers might be

but the first step to larger

conquests on the mainland. The

President of Panama, Don Juan Perez

de Guzman, immediately took steps to

recover the island. He transferred

himself to Porto Bello, embargoed an

English ship of thirty guns, the

"Concord," lying at anchor there

with licence to trade in negroes,

manned it with 350 Spaniards under

command of José Sánchez Jiménez, and

sent it to Cartagena. The governor

of Cartagena contributed several

small vessels and a hundred or more

men to the enterprise, and on 10th

August 1666 the united Spanish fleet

appeared off the shores of

Providence. On the refusal of Major

Smith to surrender, the Spaniards landed, and on 15th

August, after a three days' siege,

forced the handful of buccaneers,

only sixty or seventy in number, to

capitulate. Some of the English

defenders later deposed before

Governor Modyford that the Spaniards

had agreed to let them depart in a

barque for Jamaica. However this may

be, when the English came to lay

down their arms they were made

prisoners by the Spaniards, carried

to Porto Bello, and all except Sir

Thomas Whetstone, Major Smith and

Captain Stanley, the three English

captains, submitted to the most

inhuman cruelties. Thirty-three were

chained to the ground in a dungeon

12 feet by 10. They were forced to

work in the water from five in the

morning till seven at night, and at

such a rate that the Spaniards

themselves confessed they made one

of them do more work than any three

negroes; yet when weak for want of

victuals and sleep, they were

knocked down and beaten with cudgels

so that four or five died. "Having

no clothes, their backs were

blistered with the sun, their heads

scorched, their necks, shoulders and

hands raw with carrying stones and

mortar, their feet chopped and their

legs bruised and battered with the

irons, and their corpses were

noisome to one another." The three

English captains were carried to

Panama, and there cast into a

dungeon and bound in irons for

seventeen months.258

On 8th January 1664 Sir Richard

Fanshaw, formerly ambassador to

Portugal, had arrived in Madrid from

England to negotiate a treaty of

commerce with Spain, and if possible

to patch up a peace between the

Spanish and Portuguese crowns. He

had renewed the old demand for a

free commerce in the Indies; and the

negotiations had dragged through the

years of 1664 and 1665, hampered and

crossed by the factions in the

Spanish court, the hostile

machinations of the Dutch resident

in Madrid, and the constant rumours

of cruelties and desolations by the

freebooters in America.259

The Spanish Government insisted that

by sole virtue of the articles of

1630 there was peace on both sides

of the "Line," and that the

violences of the buccaneers in the

West Indies, and even the presence

of English colonists there, was a

breach of the articles. In this

fashion they endeavoured to reduce

Fanshaw to the position of a

suppliant for favours which they

might only out of their grace and

generosity concede. It was a

favourite trick of Spanish

diplomacy, which had been worked

many times before. The English

ambassador was, in consequence,

compelled strenuously to deny the

existence of any peace in America,

although he realised how ambiguous

his position had been rendered by

the original orders of Charles II.

to Modyford in 1664.260

After the death of Philip IV. in

1665, negotiations were renewed with

the encouragement of the Queen

Regent, and on 17th December

provisional articles were signed by

Fanshaw and the Duke de Medina de

los Torres and sent to England for

ratification.261

Fanshaw died shortly after, and Lord

Sandwich, his successor, finally

succeeded in concluding a treaty on

23rd May 1667.262

The provisions of the treaty

extended to places "where hitherto

trade and commerce hath been

accustomed," and the only privileges

obtained in America were those which

had been granted to the Low

Countries by the Treaty of Munster.

On 21st July of the same year a

general peace was concluded at Breda

between England, Holland and France.

It was in the very midst of Lord

Sandwich's negotiations that

Modyford had, as Beeston expresses

it in his Journal, declared war

against the Spaniards by the

re-issue of privateering

commissions. He had done it all in

his own name, however, so that the

king might disavow him should the

exigencies of diplomacy demand it.263

Moreover, at this same time, in the

middle of 1666, Albemarle was

writing to Modyford that

notwithstanding the negotiations, in

which, as he said, the West Indies

were not at all concerned, the

governor might still employ the

privateers as formerly, if it be for

the benefit of English interests in

the Indies.264

The news of the general peace

reached Jamaica late in 1667; yet

Modyford did not change his policy.

It is true that in February

Secretary Lord Arlington had sent

directions to restrain the

buccaneers from further acts of

violence against the Spaniards;265

but Modyford drew his own

conclusions from the contradictory

orders received from England, and

was conscious, perhaps, that he was

only reflecting the general policy

of the home government when he wrote

to Arlington:—"Truly it must be very

imprudent to run the hazard of this

place, for obtaining a

correspondence which could not but

by orders from Madrid be had.... The

Spaniards look on us as intruders

and trespassers, wheresoever they

find us in the Indies, and use us

accordingly; and were it in their

power, as it is fixed in their

wills, would soon turn us out of all

our plantations; and is it

reasonable that we should quietly

let them grow upon us until they are

able to do it? It must be force

alone that can cut in sunder that

unneighbourly maxim of their

government to deny all access to

strangers."266

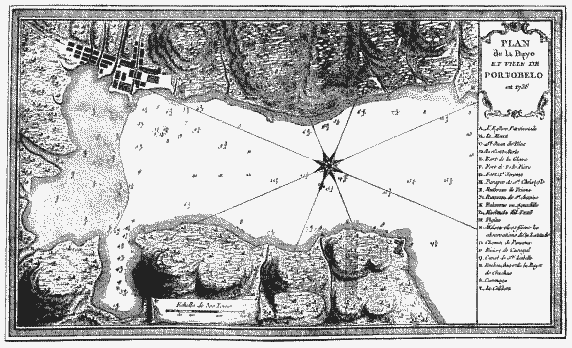

These words were very soon

translated into action, for in June

1668 Henry Morgan, with a fleet of

nine or ten ships and between 400

and 500 men, took and sacked Porto

Bello, one of the strongest cities

of Spanish America, and the emporium

for most of the European trade of

the South American continent. Henry

Morgan was a nephew of the Colonel

Edward Morgan who died in the

assault of St. Eustatius. He is said

to have been kidnapped at Bristol

while he was a mere lad and sold as

a servant in Barbadoes, whence, on

the expiration of his time, he found

his way to Jamaica. There he joined

the buccaneers and soon rose to be

captain of a ship. It was probably

he who took part in the expedition

with Morris and Jackman to Campeache

and Central America. He afterwards

joined the Curaçao armament of

Mansfield and was with the latter

when he seized the island of

Providence. After Mansfield's

disappearance Morgan seems to have

taken his place as the foremost

buccaneer leader in Jamaica, and

during the next twenty years he was one of the most

considerable men in the colony. He

was but thirty-three years old when

he led the expedition against Porto

Bello.267

In the beginning of 1668 Sir

Thomas Modyford, having had

"frequent and strong advice" that

the Spaniards were planning an

invasion of Jamaica, had

commissioned Henry Morgan to draw

together the English privateers and

take some Spanish prisoners in order

to find out if these rumours were

true. The buccaneers, according to

Morgan's own report to the governor,

were driven to the south cays of

Cuba, where being in want of

victuals and "like to starve," and

meeting some Frenchmen in a similar

plight, they put their men ashore to

forage. They found all the cattle

driven up into the country, however,

and the inhabitants fled. So the

freebooters marched twenty leagues

to Puerto Principe on the north side

of the island, and after a short

encounter, in which the Spanish

governor was killed, possessed

themselves of the place. Nothing of

value escaped the rapacity of the

invaders, who resorted to the

extremes of torture to draw from

their prisoners confessions of

hidden wealth. On the entreaty of

the Spaniards they forebore to fire

the town, and for a ransom of 1000

head of cattle released all the

prisoners; but they compelled the

Spaniards to salt the beef and carry

it to the ships.268

Morgan reported, with what degree of

truth we have no means of judging,

that seventy men had been impressed

in Puerto Principe to go against

Jamaica, and that a similar levy had been made

throughout the island. Considerable

forces, moreover, were expected from

the mainland to rendezvous at Havana

and St. Jago, with the final object

of invading the English colony.

On returning to the ships from

the sack of Puerto Principe, Morgan

unfolded to his men his scheme of

striking at the very heart of

Spanish power in the Indies by

capturing Porto Bello. The Frenchmen

among his followers, it seems,

wholly refused to join him in this

larger design, full of danger as it

was; so Morgan sailed away with only

the English freebooters, some 400 in

number, for the coasts of Darien.

Exquemelin has left us a narrative

of this exploit which is more

circumstantial than any other we

possess, and agrees so closely with

what we know from other sources that

we must accept the author's

statement that he was an

eye-witness. He relates the whole

story, moreover, in so entertaining

and picturesque a manner that he

deserves quotation.

"Captain Morgan," he says, "who

knew very well all the avenues of

this city, as also all the

neighbouring coasts, arrived in the

dusk of the evening at the place

called Puerto de Naos, distant ten

leagues towards the west of Porto

Bello.269

Being come unto this place, they

mounted the river in their ships, as

far as another harbour called Puerto

Pontin, where they came to anchor.

Here they put themselves immediately

into boats and canoes, leaving in

the ships only a few men to keep

them and conduct them the next day unto

the port. About midnight they came

to a certain place called Estera

longa Lemos, where they all went on

shore, and marched by land to the

first posts of the city. They had in

their company a certain Englishman,

who had been formerly a prisoner in

those parts, and who now served them

for a guide. Unto him, and three or

four more, they gave commission to

take the sentry, if possible, or to

kill him upon the place. But they

laid hands on him and apprehended

him with such cunning as he had no

time to give warning with his

musket, or make any other noise.

Thus they brought him, with his

hands bound, unto Captain Morgan,

who asked him: 'How things went in

the city, and what forces they had';

with many other circumstances, which

he was desirous to know. After every

question they made him a thousand

menaces to kill him, in case he

declared not the truth. Thus they

began to advance towards the city,

carrying always the said sentry

bound before them. Having marched

about one quarter of a league, they

came to the castle that is nigh unto

the city, which presently they

closely surrounded, so that no

person could get either in or out of

the said fortress.

"Being thus posted under the

walls of the castle, Captain Morgan

commanded the sentry, whom they had

taken prisoner, to speak to those

that were within, charging them to

surrender, and deliver themselves up

to his discretion; otherwise they

should be all cut in pieces, without

giving quarter to any one. But they

would hearken to none of these

threats, beginning instantly to

fire; which gave notice unto the

city, and this was suddenly alarmed.

Yet, notwithstanding, although the

Governor and soldiers of the said

castle made as great resistance as

could be performed, they were

constrained to surrender unto the

Pirates. These no sooner had taken

the castle, than they resolved to be

as good as their words, in putting

the Spaniards to the sword,

thereby to strike a terror into the

rest of the city. Hereupon, having

shut up all the soldiers and

officers as prisoners into one room,

they instantly set fire to the

powder (whereof they found great

quantity), and blew up the whole

castle into the air, with all the

Spaniards that were within. This

being done, they pursued the course

of their victory, falling upon the

city, which as yet was not in order

to receive them. Many of the

inhabitants cast their precious

jewels and moneys into wells and

cisterns or hid them in other places

underground, to excuse, as much as

were possible, their being totally

robbed. One party of the Pirates

being assigned to this purpose, ran

immediately to the cloisters, and

took as many religious men and women

as they could find. The Governor of

the city not being able to rally the

citizens, through the huge confusion

of the town, retired unto one of the

castles remaining, and from thence

began to fire incessantly at the

Pirates. But these were not in the

least negligent either to assault

him or defend themselves with all

the courage imaginable. Thus it was

observed that, amidst the horror of

the assault, they made very few shot

in vain. For aiming with great

dexterity at the mouths of the guns,

the Spaniards were certain to lose

one or two men every time they

charged each gun anew.

"The assault of this castle where

the Governor was continued very

furious on both sides, from break of

day until noon. Yea, about this time

of the day the case was very dubious

which party should conquer or be

conquered. At last the Pirates,

perceiving they had lost many men

and as yet advanced but little

towards the gaining either this or

the other castles remaining, thought

to make use of fireballs, which they

threw with their hands, designing,

if possible, to burn the doors of

the castle. But going about to put

this in execution, the Spaniards

from the walls let fall great

quantity of stones and earthen pots

full of powder and other combustible

matter, which forced them to desist

from that attempt. Captain Morgan,

seeing this generous defence made by

the Spaniards, began to despair of

the whole success of the enterprise.

Hereupon many faint and calm

meditations came into his mind;

neither could he determine which way

to turn himself in that straitness

of affairs. Being involved in these

thoughts, he was suddenly animated

to continue the assault, by seeing

the English colours put forth at one

of the lesser castles, then entered

by his men, of whom he presently

after spied a troop that came to

meet him proclaiming victory with

loud shouts of joy. This instantly

put him upon new resolutions of

making new efforts to take the rest

of the castles that stood out

against him; especially seeing the

chief citizens were fled unto them,

and had conveyed thither great part

of their riches, with all the plate

belonging to the churches, and other

things dedicated to divine service.

"To this effect, therefore, he

ordered ten or twelve ladders to be

made, in all possible haste, so

broad that three or four men at once

might ascend by them. These being

finished, he commanded all the

religious men and women whom he had

taken prisoners to fix them against

the walls of the castle. Thus much

he had beforehand threatened the

Governor to perform, in case he

delivered not the castle. But his

answer was: 'He would never

surrender himself alive.' Captain

Morgan was much persuaded that the

Governor would not employ his utmost

forces, seeing religious women and

ecclesiastical persons exposed in

the front of the soldiers to the

greatest dangers. Thus the ladders,

as I have said, were put into the

hands of religious persons of both

sexes; and these were forced, at the

head of the companies, to raise and

apply them to the walls. But Captain

Morgan was deceived in his judgment

of this design. For the Governor,

who acted like a brave and

courageous soldier, refused not, in

performance of his duty, to use his

utmost endeavours to destroy

whosoever came near the walls. The

religious men and women ceased not

to cry unto him and beg of him by

all the Saints of Heaven he would

deliver the castle, and hereby spare

both his and their own lives. But

nothing could prevail with the

obstinacy and fierceness that had

possessed the Governor's mind. Thus

many of the religious men and nuns

were killed before they could fix

the ladders. Which at last being

done, though with great loss of the

said religious people, the Pirates

mounted them in great numbers, and

with no less valour; having

fireballs in their hands, and

earthen pots full of powder. All

which things, being now at the top

of the walls, they kindled and cast

in among the Spaniards.

"This effort of the Pirates was

very great, insomuch as the

Spaniards could no longer resist nor

defend the castle, which was now

entered. Hereupon they all threw

down their arms, and craved quarter

for their lives. Only the Governor

of the city would admit or crave no

mercy; but rather killed many of the

Pirates with his own hands, and not

a few of his own soldiers, because

they did not stand to their arms.

And although the Pirates asked him

if he would have quarter, yet he

constantly answered: 'By no means; I

had rather die as a valiant soldier,

than be hanged as a coward.' They

endeavoured as much as they could to

take him prisoner. But he defended

himself so obstinately that they

were forced to kill him;

notwithstanding all the cries and

tears of his own wife and daughter,

who begged of him upon their knees

he would demand quarter and save his

life. When the Pirates had possessed

themselves of the castle, which was

about night, they enclosed therein

all the prisoners they had taken,

placing the women and men by

themselves, with some guards upon

them. All the wounded were put into

a certain apartment by itself, to

the intent their own complaints might be the cure of

their diseases; for no other was

afforded them.

"This being done, they fell to

eating and drinking after their

usual manner; that is to say,

committing in both these things all

manner of debauchery and excess....

After such manner they delivered

themselves up unto all sort of

debauchery, that if there had been

found only fifty courageous men,

they might easily have re-taken the

city, and killed all the Pirates.

The next day, having plundered all

they could find, they began to

examine some of the prisoners (who

had been persuaded by their

companions to say they were the

richest of the town), charging them

severely to discover where they had

hidden their riches and goods. But

not being able to extort anything

out of them, as they were not the

right persons that possessed any

wealth, they at last resolved to

torture them. This they performed

with such cruelty that many of them

died upon the rack, or presently

after. Soon after, the President of

Panama had news brought him of the

pillage and ruin of Porto Bello.

This intelligence caused him to

employ all his care and industry to

raise forces, with design to pursue

and cast out the Pirates from

thence. But these cared little for

what extraordinary means the

President used, as having their

ships nigh at hand, and being

determined to set fire unto the city

and retreat. They had now been at

Porto Bello fifteen days, in which

space of time they had lost many of

their men, both by the unhealthiness

of the country and the extravagant

debaucheries they had committed.270

"Hereupon they prepared for a

departure, carrying on board their ships all

the pillage they had gotten. But,

before all, they provided the fleet

with sufficient victuals for the

voyage. While these things were

getting ready, Captain Morgan sent

an injunction unto the prisoners,

that they should pay him a ransom

for the city, or else he would by

fire consume it to ashes, and blow

up all the castles into the air.

Withal, he commanded them to send

speedily two persons to seek and

procure the sum he demanded, which

amounted to one hundred thousand

pieces of eight. Unto this effect,

two men were sent to the President

of Panama, who gave him an account

of all these tragedies. The

President, having now a body of men

in readiness, set forth immediately

towards Porto Bello, to encounter

the Pirates before their retreat.

But these people, hearing of his

coming, instead of flying away, went

out to meet him at a narrow passage

through which of necessity he ought

to pass. Here they placed an hundred

men very well armed; the which, at

the first encounter, put to flight a

good party of those of Panama. This

accident obliged the President to

retire for that time, as not being

yet in a posture of strength to

proceed any farther. Presently after

this rencounter he sent a message

unto Captain Morgan to tell him:

'That in case he departed not

suddenly with all his forces from

Porto Bello, he ought to expect no

quarter for himself nor his

companions, when he should take

them, as he hoped soon to do.'

Captain Morgan, who feared not his

threats knowing he had a secure

retreat in his ships which were nigh

at hand, made him answer: 'He would

not deliver the castles, before he

had received the contribution money

he had demanded. Which in case it

were not paid down, he would

certainly burn the whole city, and

then leave it, demolishing

beforehand the castles and killing

the prisoners.'

"The Governor of Panama perceived

by this answer that no means would

serve to mollify the hearts of the

Pirates, nor reduce them to reason.

Hereupon he determined to leave

them; as also those of the city,

whom he came to relieve, involved in

the difficulties of making the best

agreement they could with their

enemies.271

Thus, in a few days more, the

miserable citizens gathered the

contribution wherein they were

fined, and brought the entire sum of

one hundred thousand pieces of eight

unto the Pirates, for a ransom of

the cruel captivity they were fallen

into. But the President of Panama,

by these transactions, was brought

into an extreme admiration,

considering that four hundred men

had been able to take such a great

city, with so many strong castles;

especially seeing they had no pieces

of cannon, nor other great guns,

wherewith to raise batteries against

them. And what was more, knowing

that the citizens of Porto Bello had

always great repute of being good

soldiers themselves, and who had

never wanted courage in their own

defence. This astonishment was so

great, that it occasioned him, for

to be satisfied therein, to send a

messenger unto Captain Morgan,

desiring him to send him some small

pattern of those arms wherewith he

had taken with such violence so

great a city. Captain Morgan

received this messenger very kindly,

and treated him with great civility.

Which being done, he gave him a

pistol and a few small bullets of

lead, to carry back unto the

President, his Master, telling him

withal: 'He desired him to accept

that slender pattern of the arms

wherewith he had taken Porto Bello

and keep them for a twelvemonth;

after which time he promised to come

to Panama and fetch them away.' The

governor of Panama returned the

present very soon unto Captain

Morgan, giving him thanks for the

favour of lending him such weapons

as he needed not, and withal sent him a ring of gold,

with this message: 'That he desired

him not to give himself the labour

of coming to Panama, as he had done

to Porto Bello; for he did certify

unto him, he should not speed so

well here as he had done there.'

"After these transactions,

Captain Morgan (having provided his

fleet with all necessaries, and

taken with him the best guns of the

castles, nailing the rest which he

could not carry away) set sail from

Porto Bello with all his ships. With

these he arrived in a few days unto

the Island of Cuba, where he sought

out a place wherein with all quiet

and repose he might make the

dividend of the spoil they had

gotten. They found in ready money

two hundred and fifty thousand

pieces of eight, besides all other

merchandises, as cloth, linen, silks

and other goods. With this rich

purchase they sailed again from

thence unto their common place of

rendezvous, Jamaica. Being arrived,

they passed here some time in all

sorts of vices and debauchery,

according to their common manner of

doing, spending with huge

prodigality what others had gained

with no small labour and toil."272

Morgan and his officers, on their

return to Jamaica in the middle of

August, made an official report

which places their conduct in a

peculiarly mild and charitable

light,273

and forms a sharp contrast to the

account left us by Exquemelin.

According to Morgan the town and

castles were restored "in as good

condition as they found them," and

the people were so well treated that

"several ladies of great quality and

other prisoners" who were offered

"their liberty to go to the

President's camp, refused, saying

they were now prisoners to a person

of quality, who was more tender of

their honours than they doubted to

find in the president's camp, and so

voluntarily continued with them till

the surrender of the town and

castles." This scarcely tallies with

what we know of the manners of the

freebooters, and Exquemelin's

evidence is probably nearer the

truth. When Morgan returned to

Jamaica Modyford at first received

him somewhat doubtfully, for

Morgan's commission, as the Governor

told him, was only against ships,

and the Governor was not at all sure

how the exploit would be taken in

England. Morgan, however, had

reported that at Porto Bello, as

well as in Cuba, levies were being

made for an attack upon Jamaica, and

Modyford laid great stress upon this

point when he forwarded the

buccaneer's narrative to the Duke of

Albemarle.

The sack of Porto Bello was

nothing less than an act of open war

against Spain, and Modyford, now

that he had taken the decisive step,

was not satisfied with half

measures. Before the end of October

1668 the whole fleet of privateers,

ten sail and 800 men, had gone out

again under Morgan to cruise on the

coasts of Caracas, while Captain

Dempster with several other vessels

and 300 followers lay before

Havana and along the shores of

Campeache.274

Modyford had written home repeatedly

that if the king wished him to

exercise any adequate control over

the buccaneers, he must send from

England two or three nimble

fifth-rate frigates to command their

obedience and protect the island

from hostile attacks. Charles in

reply to these letters sent out the

"Oxford," a frigate of thirty-four

guns, which arrived at Port Royal on

14th October. According to Beeston's

Journal, it brought instructions

countenancing the war, and

empowering the governor to

commission whatever persons he

thought good to be partners with His

Majesty in the plunder, "they

finding victuals, wear and tear."275

The frigate was immediately

provisioned for a several months'

cruise, and sent under command of

Captain Edward Collier to join

Morgan's fleet as a private

ship-of-war. Morgan had appointed

the Isle la Vache, or Cow Island, on

the south side of Hispaniola, as the

rendezvous for the privateers; and

thither flocked great numbers, both

English and French, for the name of

Morgan was, by his exploit at Porto

Bello, rendered famous in all the

neighbouring islands. Here, too,

arrived the "Oxford" in December.

Among the French privateers were two

men-of-war, one of which, the "Cour

Volant" of La Rochelle, commanded by

M. la Vivon, was seized by Captain

Collier for having robbed an English

vessel of provisions. A few days

later, on 2nd January, a council of

war was held aboard the "Oxford,"

where it was decided that the

privateers, now numbering about 900

men, should attack Cartagena. While

the captains were at dinner on the

quarter-deck, however, the frigate

blew up, and about 200 men,

including five captains, were lost.276

"I was eating my dinner with the rest," writes the

surgeon, Richard Browne, "when the

mainmasts blew out, and fell upon

Captains Aylett, Bigford, and

others, and knocked them on the

head; I saved myself by getting

astride the mizzenmast." It seems

that out of the whole ship only

Morgan and those who sat on his side

of the table were saved. The

accident was probably caused by the

carelessness of a gunner. Captain

Collier sailed in la Vivon's ship

for Jamaica, where the French

captain was convicted of piracy in

the Admiralty Court, and reprieved

by Governor Modyford, but his ship

confiscated.277

Morgan, from the rendezvous at

the Isle la Vache, had coasted along

the southern shores of Hispaniola

and made several inroads upon the

island for the purpose of securing

beef and other provisions. Some of

his ships, meanwhile, had been

separated from the body of the

fleet, and at last he found himself

with but eight vessels and 400 or

500 men, scarcely more than half his

original company. With these small

numbers he changed his resolution to

attempt Cartagena, and set sail for

Maracaibo, a town situated on the

great lagoon of that name in

Venezuela. This town had been

pillaged in 1667, just before the

peace of Aix-la-Chapelle, by 650

buccaneers led by two French

captains, L'Olonnais and Michel le

Basque, and had suffered all the

horrors attendant upon such a visit.

In March 1669 Morgan appeared at the

entrance to the lake, forced the

passage after a day's hot

bombardment, dismantled the fort

which commanded it, and entered

Maracaibo, from which the

inhabitants had fled before him. The buccaneers sacked the

town, and scoured the woods in

search of the Spaniards and their

valuables. Men, women and children

were brought in and cruelly tortured

to make them confess where their

treasures were hid. Morgan, at the

end of three weeks, "having now got

by degrees into his hands about 100

of the chief families," resolved to

go to Gibraltar, near the head of

the lake, as L'Olonnais had done

before him. Here the scenes of

inhuman cruelty, "the tortures,

murders, robberies and such like

insolences," were repeated for five

weeks; after which the buccaneers,

gathering up their rich booty,

returned to Maracaibo, carrying with

them four hostages for the ransom of

the town and prisoners, which the

inhabitants promised to send after

them. At Maracaibo Morgan learnt

that three large Spanish men-of-war

were lying off the entrance of the

lake, and that the fort, in the

meantime, had been armed and manned

and put into a posture of defence.

In order to gain time he entered

into negotiations with the Spanish

admiral, Don Alonso del Campo y

Espinosa, while the privateers

carefully made ready a fireship

disguised as a man-of-war. At dawn

on 1st May 1669, according to

Exquemelin, they approached the

Spanish ships riding at anchor

within the entry of the lake, and

sending the fireship ahead of the

rest, steered directly for them. The

fireship fell foul of the

"Almirante," a vessel of forty guns,

grappled with her and set her in

flames. The second Spanish ship,

when the plight of the Admiral was

discovered, was run aground and

burnt by her own men. The third was

captured by the buccaneers. As no

quarter was given or taken, the loss

of the Spaniards must have been

considerable, although some of those

on the Admiral, including Don

Alonso, succeeded in reaching shore.

From a pilot picked up by the

buccaneers, Morgan learned that in

the flagship was a great quantity of

plate to the value of 40,000 pieces

of eight. Of this he succeeded in recovering about

half, much of it melted by the force

of the heat. Morgan then returned to

Maracaibo to refit his prize, and

opening negotiations again with Don

Alonso, he actually succeeded in

obtaining 20,000 pieces of eight and

500 head of cattle as a ransom for

the city. Permission to pass the

fort, however, the Spaniard refused.

So, having first made a division of

the spoil,278

Morgan resorted to an ingenious

stratagem to effect his egress from

the lake. He led the Spaniards to

believe that he was landing his men

for an attack on the fort from the

land side; and while the Spaniards

were moving their guns in that

direction, Morgan in the night, by

the light of the moon, let his ships

drop gently down with the tide till

they were abreast of the fort, and

then suddenly spreading sail made

good his escape. On 17th May the

buccaneers returned to Port Royal.

These events in the West Indies

filled the Spanish Court with

impotent rage, and the Conde de

Molina, ambassador in England, made

repeated demands for the punishment

of Modyford, and for the restitution

of the plate and other captured

goods which were beginning to flow

into England from Jamaica. The

English Council replied that the

treaty of 1667 was not understood to

include the Indies, and Charles II.

sent him a long list of complaints

of ill-usage to English ships at the

hands of the Spaniards in America.279

Orders seem to have been sent to

Modyford, however, to stop

hostilities, for in May 1669

Modyford again called in all

commissions,280

and Beeston writes in his Journal,

under 14th June, that peace was

publicly proclaimed with the

Spaniards. In November, moreover, the governor

told Albemarle that most of the

buccaneers were turning to trade,

hunting or planting, and that he

hoped soon to reduce all to peaceful

pursuits.281

The Spanish Council of State, in the

meantime, had determined upon a

course of active reprisal. A

commission from the queen-regent,

dated 20th April 1669, commanded her

governors in the Indies to make open

war against the English;282

and a fleet of six vessels, carrying

from eighteen to forty-eight guns,

was sent from Spain to cruise

against the buccaneers. To this

fleet belonged the three ships which

tried to bottle up Morgan in Lake

Maracaibo. Port Royal was filled

with report and rumour of English

ships captured and plundered, of

cruelties to English prisoners in

the dungeons of Cartagena, of

commissions of war issued at Porto

Bello and St. Jago de Cuba, and of

intended reprisals upon the

settlements in Jamaica. The

privateers became restless and spoke

darkly of revenge, while Modyford,

his old supporter the Duke of

Albemarle having just died, wrote

home begging for orders which would

give him liberty to retaliate.283

The last straw fell in June 1670,

when two Spanish men-of-war from St.

Jago de Cuba, commanded by a

Portuguese, Manuel Rivero Pardal,

landed men on the north side of the

island, burnt some houses and

carried off a number of the

inhabitants as prisoners.284

On 2nd July the governor and council

issued a commission to Henry Morgan,

as commander-in-chief of

all ships of war belonging to

Jamaica, to get together the

privateers for the defence of the

island, to attack, seize and destroy

all the enemy's vessels he could

discover, and in case he found it

feasible, "to land and attack St.

Jago or any other place where ...

are stores for this war or a

rendezvous for their forces." In the

accompanying instructions he was

bidden "to advise his fleet and

soldiers that they were upon the old

pleasing account of no purchase, no

pay, and therefore that all which is

got, shall be divided amongst them,

according to the accustomed rules."285

Morgan sailed from Jamaica on

14th August 1670 with eleven vessels

and 600 men for the Isle la Vache,

the usual rendezvous, whence during

the next three months squadrons were

detailed to the coast of Cuba and

the mainland of South America to

collect provisions and intelligence.

Sir William Godolphin was at that

moment in Madrid concluding articles

for the establishment of peace and

friendship in America; and on 12th

June Secretary Arlington wrote to

Modyford that in view of these

negotiations his Majesty commanded

the privateers to forbear all

hostilities on land against the

Spaniards.286

These orders reached Jamaica on 13th

August, whereupon the governor

recalled Morgan, who had sailed from

the harbour the day before, and

communicated them to him, "strictly

charging him to observe the same and